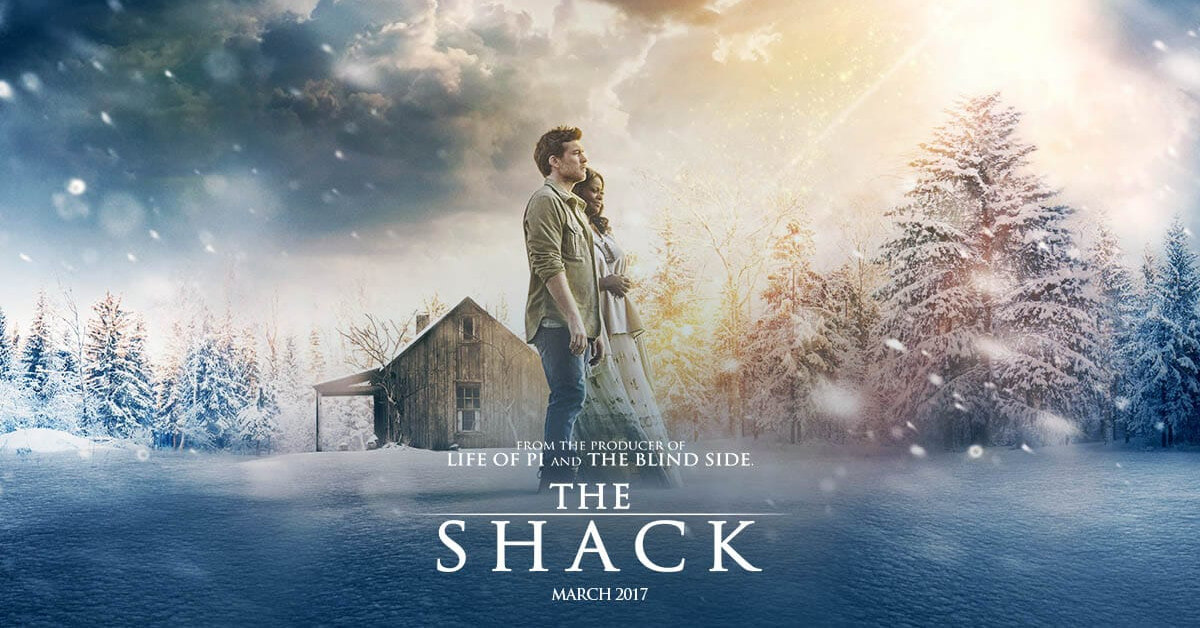

It’s hard to throw a stone in the Christian blogosphere right now without hitting a review of The Shack, the bestselling novel by Paul Young which was just released as a motion picture. And if you’re reading evangelical or Reformed writers, the reviews are going to be pretty uniformly negative—a negativity which finds justification in Young’s just-released Lies We Believe About God, which explicitly teaches the unbiblical and even heretical ideas which critics saw woven into the fiction of The Shack.

For what it’s worth, allow me to join my voice to the chorus saying that The Shack should not be on a Christian’s reading list. Yes, it has a worthy goal (showing the love of God amid the realities of suffering and pain), and yes, it gets some things right, but it also gets some things badly, badly wrong. It is true that it is “only a story,” but story can influence and shape us just as powerfully as more direct teaching. In fact, bad theology in fictional form can actually be more dangerous, as it digs deeper into our mind and is harder to recognize than straightforward false teaching.

But my interest today isn’t really in The Shack itself. If you want some good, biblical perspectives on the book, check out the articles I linked above. My interest, rather, is in what makes the God of The Shack so appealing.

I recently came across a defense of the book by Wayne Jacobsen, who collaborated with Young to write and publish The Shack. Jacobsen explains that the story is about “a loving Father finding his way through all the pain, loss, and false accusations to reconnect with one of his children who was lost in his depression.” He asks, “Who is God really? Is he an angry deity needing to be appeased by the submission of his fearful subjects, or is he a loving Abba winning people into his reality through tenderness and compassion?… The amount of email, and personal conversations I have had with people over the last decade tells me we got enough of this story right to provoke people to think about a loving God. Time and again I hear of people who had all but rejected God in the pain of their own lives, rediscovering how much God loves them by reading of this book.”

By all accounts, the God of The Shack is indeed “a loving Abba winning people into his reality through tenderness and compassion.” In fact, that’s all he is. The book’s version of God the Father, a motherly woman referred to as Papa (yes, you read that correctly), is a being of tenderness, compassion, and not much else. Papa isn’t interested in rules or religion. She speaks of “the wonder of tears” and the need for “relationships of love and respect.” She declares, “Because you are important, everything you do is important. Every time you forgive, the universe changes; every time you reach out and touch a heart or a life, the world changes; with every kindness and service, seen or unseen, my purposes are accomplished and nothing will be the same again.” Papa is full of love and eager for relationship with hurting humans, and she plays those two notes for 250 pages.

My point here is not that Young is altogether wrong about God’s love. In fact, he gets a good deal right. The Psalmist’s words, “You have kept count of my tossings; put my tears in your bottle. Are they not in your book?” would not feel out of place in The Shack. But set aside for the moment the question of how accurately Young portrays God’s love in his book. What I find striking is how little else he portrays. And 20 million readers later, The Shack makes it clear that the modern world wants a God who is nothing but tenderness and compassion; an encouraging deity who is little more than a listening ear and a warm smile.

If that seems obvious, I would humbly submit that we too are products of the modern world. For most of human history, a wish-fulfillment God would not have looked much like The Shack‘s amalgamation of therapist and friend. That is because, for most of history, the human race has had a much more vivid understanding of who our enemies are.

The Apostle Peter warned his readers, “Be sober-minded; be watchful. Your adversary the devil prowls around like a roaring lion, seeking someone to devour” (I Pet 5:8). Paul urged his readers to “Put on the whole armor of God, that you may be able to stand against the schemes of the devil” (Eph 6:11). This is martial, perilous language, because the Bible is quite plain about the vulnerability of men and women who have sin within them, Satan against them, and a fallen world around them.

For most of human history, that vulnerability was easy to see. Death was an ever-present threat, whether from disease and privation or from the violence of other men. Sin was a plain reality, in oneself and others. And behind it all loomed a vividly conceived spiritual reality with as many foes as friends. In such a world, calling God a “very present help in trouble” rings as much with martial energy as it does with empathy.

Contrast that with today, where technology and civilization have chased away nearly every threat to human wellbeing, banishing death itself into the far reaches of old age or freak accident; where materialistic science has turned Satan and the demonic into trick-or-treating costumes; where Freud has assured us that sin is an outmoded idea and what we really need is simply to embrace our natural selves. In a world where the most formidable enemy we expect to encounter is someone who roots for a rival sports team, the idea of a God who is mighty, fearful, even dangerous, falls somewhere between needless and ridiculous. All we really want is a comfortable cosmic Mother who will encourage our dreams, listen to our troubles, and heal our hurts.

Now, we ought to pause here to note that our God is comforting and compassionate and tender. The radical, self-abasing love of the God of Hosea or Philippians 2:5-8 (“who emptied himself, taking the form of a servant…”) surpasses anything The Shack portrays. But the fact that our culture is so eager for a God who is nothing but comfort and compassion and tenderness says something troubling about our perception of the world. Because we don’t actually live in a different world from our forefathers. Sin, Satan, and death are no less our enemies than theirs. The devil still prowls, your sin nature is no less cancerous because Sigmund Freud doesn’t believe in it, and you and I will die as surely as every other human who has lived since Adam and Eve first heard their divine sentence in the Garden. The fact that we no longer want a strong, triumphant God says nothing about our reality, but everything about our blindness.

If millions of people have eaten up The Shack and found nothing wanting in its portrait of the King of kings and Lord of lords, that ultimately speaks to a failure of the church—not just to teach about the nature of God, but to warn of the wolves who should drive the sheep to their shepherd. Perhaps if we each took more risks for the Kingdom, walked more by faith and less by sight, we would be able to speak with greater conviction of the joy and comfort of having a God who holds our hand in his… and has a sword in the other.