This week, my Evidence for God series will take a second look at arguments based on the appearance of design, sometimes called teleological arguments, from the Greek word telos, which means “design” or “purpose.” Last week, we looked at how the essential structure of the universe makes life possible through “fine-tuning” which cannot be explained through mere chance. Today, I want to move beyond the possibility of life to consider the actual life forms we see around us. There are two ways in which biology demands a designing intelligence: First, the complexity of biological information contained in even the most basic life form, and second, the “irreducible complexity” of biological structures which cannot be explained through evolutionary processes.

What About Evolution?

When we talk about the appearance of design in biology, we have to start by considering the theory of evolution. Every scientist would agree that living creatures seem to have been uniquely designed for their environments. In fact, the famous evolutionist Richard Dawkins defined biology as “the study of complicated things that appear to have been designed for a purpose.” The key word in that definition, of course, is “appear.” For the last two hundred years, Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution has offered a way to explain the appearance of design without requiring a designer. Evolution postulates that natural processes mold species over time, through adaptation and the pressure to survive, so that animals look like they were designed for their particular ecological niche. In reality, though, this “design” is merely the result of a process of natural selection whereby the best-adapted survive and reproduce while the rest perish, removing their less-fit genes from future generations.

Evolution is obviously, indisputably true as an explanation of how species adapt to their environments. Any competent biologist could list a dozen present-day examples off the top of his head. My personal favorite is the story of a particular species of cricket whose numbers plummeted when a predatory fly was introduced to their island home. The fly targeted male crickets by listening for their chirping and swiftly consumed the majority of the male population. However, a few males had a mutation which left them unable to sing. Ordinarily, this would have made them less likely to reproduce and the mutation would have died out, but with the chirping males being slaughtered, the mute crickets found a ready supply of females in need of mates. They reproduced, passing on their chirpless genes, and within a few years the cricket population had adapted to the new predator by losing the ability to sing. It’s really quite remarkable, and it is just one of many stories of observable present-day evolution. Frankly, for a theist, evolution is yet another reason to praise God for his wisdom in designing a way for species to route around new challenges and seek out new opportunities in their environments.

The question, of course, is whether Darwin and his modern-day adherents are correct in using this evolutionary process to explain all biological diversity. Certainly, a cricket can lose its chirp; a moth species can change color, or the shape of a finch’s beak can gradually morph, to use other famous examples. But can we trace an evolutionary path from bacteria through fish to primates to your Uncle Bob? Evolution into new and radically different species is something else, and it is an inference rather than an observation—human science operates on too short a timescale to observe such long-range evolution if it does in fact occur.

Personally, I prefer to avoid getting into debates over the general plausibility of evolution. There are a few reasons for this. First, I (and most of us on both sides of the question) simply lack the scientific expertise to effectively evaluate the evidence. Second, though I hold to literal, seven-day creation, I do believe that evidence suggests God used evolution to bring about some of the biological diversity in the world today. Together, these considerations make debate about the overall theory of evolution challenging and generally fruitless, in my opinion.

But that doesn’t mean we need to leave evolution unchallenged as an answer to every biological question. If there are some questions which even a generous estimation of evolution cannot answer, those areas offer yet another argument for the necessity of a supernatural creator. And that brings us back to the two areas of apparent design which I mentioned above.

Someone Designed the First Cell

If you don’t believe that God created life, then you have to believe that at some point in the distant past, nonliving matter spontaneously became alive. At first glance that sounds insane, but, at second glance, it’s a bit more plausible since biological organisms are ultimately composed of nonliving matter. All the bits and pieces within a living cell can be found elsewhere in nature, so it is true that the raw material was on hand to assemble the hypothetical first cell out of random chemicals. However, it’s the third glance that really causes problems for the materialist.

Let’s stipulate that matter somehow exists (though, as we saw two weeks ago, that’s inexplicable if there is no supernatural creator). And let’s stipulate that space, time, and matter are configured so biological life is theoretically possible (though, as we saw last week, that’s inexplicable if there is no supernatural creator). So we now have a mass of raw material in the form of miscellaneous chemicals which, if configured properly, could become the universe’s first living unicellular organism.

The “configured properly” part is going to be a bit of a challenge.

Every single cell is a collection of physical structures (membrane, ribosomes, etc.) which are built by proteins that were created out of amino acids from information transcribed in RNA strands by DNA chains. Let me say that again: Every single cell is a collection of physical structures which are built by proteins that were created out of amino acids from information transcribed in RNA strands by DNA chains. If that sounds very complicated, that is because it is very complicated.

Let’s start at the DNA end of things. DNA molecules hold all the information needed to build and run a cell, physically encoded in a sort of biological Morse code created by different patterns of four nucleotide bases called adenine, thymine, guanine, and cytosine. Just like dots and dashes convey information in Morse code, the A, T, G, and C bases carry all the information needed for cellular life. These individual bases combine into genes, which are sections of DNA which carry information for some particular trait. Each gene typically consists of tens of thousands of A, T, G, and C bases. Think of the bases as individual letters and each gene as a chapter in a very long book.

How long? Well, a typical single-celled organism, like E. coli for example, has about 5,000 genes. The simplest known unicellular organism which is able to survive and replicate on its own is Mycoplasma genitalium, with just 482 genes containing about 580,000 nucleotide base pairs. When scientists recently tried to replicate Mycoplasma genitalium‘s genetic information by computer, it took 128 computers running nearly 10 hours to do the job.

Once our hypothetical first cell has randomly assembled hundreds of thousands of bits of molecular data into hundreds of genes that just happen to contain a blueprint for how to build a living cell, we also need to have some RNA, an equally complex molecule which copies the DNA data and then uses it to assemble amino acids (oh, yes, we need the correct amino acids right there too) into proteins which actually form the structure and perform the functions of the cell. And all this needs to be take place within a cellular membrane composed of phospholipid molecules to hold everything together so you actually have a cell rather than a collection of random bits floating around.

Crediting blind chance with the origin of cellular life is like arguing that you could put hundreds of thousands of Legos into a boxcar and shake it until the Legos assembled into a robot… which would then naturally build another robot… which would then work together to plant a garden.

I don’t have that kind of faith.

Biological Systems Which Could Not Have Evolved

Until we get our first cell, evolution can offer the atheist no help at all, because survival of the fittest can only shape species once there are species to shape. Evolution works through adaption, survival, and reproduction, all of which require living organisms. But once we (somehow) have our initial cellular life, it might seem like the materialist has hit clear sailing. If we grant that evolution can transform species over time, and if we personally lack the scientific knowledge to debate exactly how much inter-species change it could produce, it would appear that we are ill-prepared to suggest that biological diversity is another sign that there is a creator. Of course, even if that was the case, the other arguments we have surveyed are strong enough that we can be quite comfortable defending the natural-revelation case for theism without even mentioning biological diversity, but in fact there is a strong case to be made here as well.

The strongest evidence for design within biological organisms is the theory called “irreducible complexity.” In a nutshell, an irreducibly complex biological structure is something—the blood-clotting process and the bacterial flagellum are often cited as examples—which can only work if all of its components are in place. Take away one part, and the whole thing becomes useless.

Why is that significant? Because evolution depends upon relatively gradual change. As generations of sea creatures crawl onto land, their flippers turn into legs over thousands of years. As generations of apes begin increasingly depending on their minds to survive, their brains grow and change. And so on. The key is that each stage in the transition offers its own survival benefit. A slightly more leg-like flipper will help a former sea creature move a bit faster. A slightly larger brain will help an ape think a bit better. Therefore, those changes would make their possessors more likely to survive and pass along the “partway” modification, ready for the next adaption to take things further. If, on the other hand, a mutation offered no benefit, it would simply die out. Thus, if a biological system is irreducibly complex, there would be no way for it to evolve because evolutionary pressures would not create the intermediate steps needed to develop the various components that would make the whole system work.

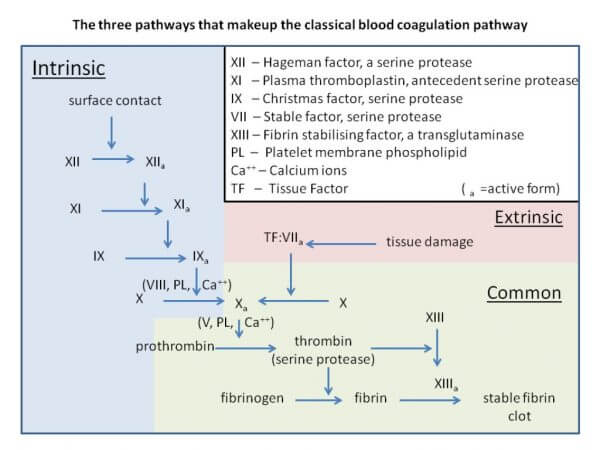

The chemical cascade which allows our blood to clot is one of my favorite examples of irreducible complexity. If you think about it, the fact that our blood clots is quite odd. In general, if you puncture a pressurized tube containing liquid (which is what a blood vessel is), the liquid drains out until none is left. In fact, that is what happens to hemophiliacs. Yet, for most people, a cut is no big deal because we can take it for granted that within a few minutes a scab will form to stop the bleeding. This is because of a highly complex biochemical chain reaction which takes place within our blood. There is literally no space to detail here the convoluted chemical cascade which keeps you from bleeding to death every time you get a paper cut, but you can read a longer description of this and other irreducibly complex biochemical systems in Darwin’s Black Box by Michael Behe. For our purposes, I’ll simply point you to this little diagram which summarizes the blood clotting process (source):

Blood clotting requires more than a dozen proteins and enzymes to activate one another, modify one another, stick together and pull apart, all in precisely calibrated dance which, if it went wrong, would either leave the wound to bleed dry or, alternately, would cause the entire blood supply to coagulate, causing a massive heart attack. Taken piece by piece, the individual components do no good, and most of the parts are needed before the system can work at all. In other words, it’s an irreducibly complex system and there is absolutely no way for evolution to explain it. (And evolutionists haven’t, though they keep trying.)

Exactly what constitutes an irreducibly complex biological system is debatable, but scientists have proposed quite a few possibilities, like bacterial cilia and flagella, human eyesight and elements of the immune system, and even the cellular structures I mentioned above. If even a single one of these systems truly cannot be explained by the evolutionary process, then, once again, we are left with something which testifies that it must have been designed—and we all know that design requires a designer.