With 4th of July festivities under way and flags and tri-colored streamers filling the air, it is a good time to consider the much-maligned virtue of patriotism. Along with many other natural affections, patriotism has been staggered by successive blows from modernism, which sees such emotions as irrational and useless, and postmodernism, which sees them as dangerous.

For sterile, scientific modernism, the idea of having particular pride in one’s country is simply absurd. After all, one’s place of birth is mere happenstance. Every nation has its merits and demerits, and comparison between our own country and the rest of the world will never be entirely complementary. As Virginia Woolf wrote grimly of her own land, those tempted to an irrational local enthusiasm should “compare English painting with French painting; English music with German music; English literature with Greek literature… When all these comparisons have been faithfully made by the use of reason, the outsider will find herself in possession of very good reasons for her indifference.”

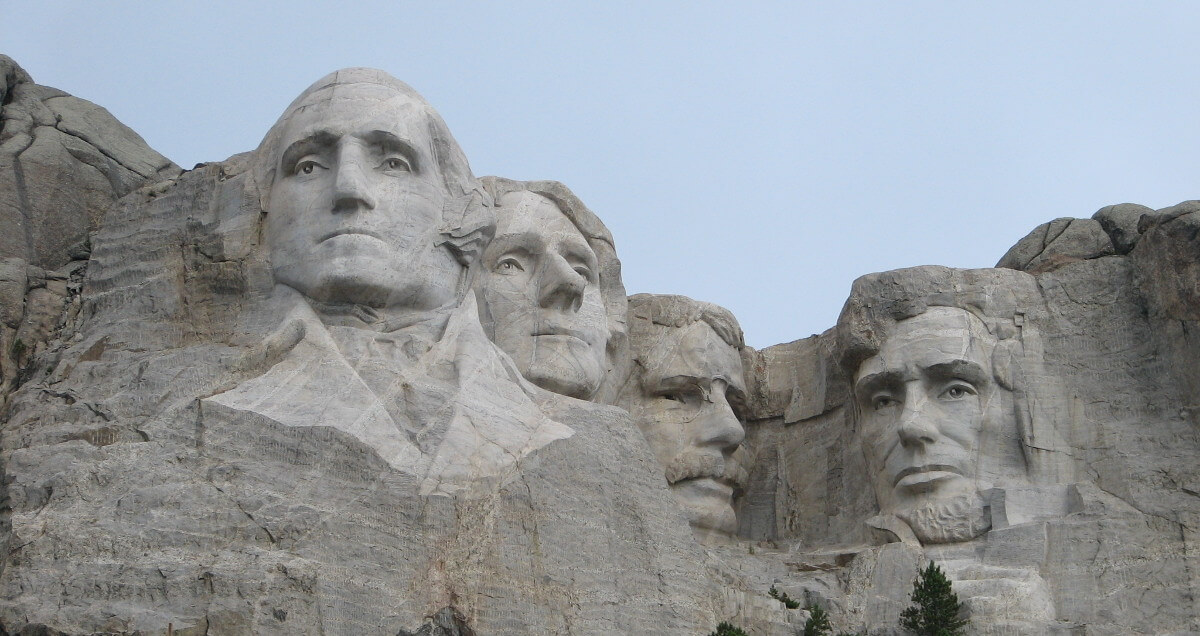

We might choose somewhat different criteria from those which appeal to Ms. Woolf, but surely anyone would agree that no particular nation can be declared “best” by anything but the most narrow and specialized comparison. (I suppose America might really be best at software design, or Canada at maple syrup production, but somehow that seems a rather weak foundation for patriotic enthusiasm.) Every country has its heroes and villains, and every history has black sections along with the white, with much grey in between. When you get right down to it, one flag looks very much like any other, and the idea of dying in a heap on a hill simply because a flag with a particular design happens to be planted there does seem rather odd.

But if just-the-facts modernism cannot understand patriotism, postmodernism believes it understands it all too well. For the postmodern, ever cautious of sweeping causes and unchanging convictions, patriotism is just another -ism to make us hate and hurt one another. “Imagine there’s no countries / It isn’t hard to do / Nothing to kill or die for…” Postmodernism fears that all images of a crowd saluting the flag are essentially alike, whether the arms are crooked or straight and whether the flag bears stars or swastika.

And so one of the most universal and natural human emotions is hustled off to the dustbin of history. It takes a good deal of conditioning and effort not to feel a certain thrill when the stars and stripes snap in the breeze and the national anthem plays, but our schools and media have been hard at work to produce just such a self-conscious deadening. Of course, not everyone has been compliant. When we are told that civic virtue can no longer keep company with patriotism, tribal instinct will lead some of us to clutch the flag and wave goodbye to civic virtue. (A healthier patriotism would have been much less susceptible to a certain presidential candidate’s promises to Make America Great Again by any means necessary.)

But what should patriotism mean to Christians who are called to be in, but not of, the world (John 17:14-16)? Certainly, our primary allegiance is not to this world and its kingdoms, but a thing can be valuable without being primary. Perhaps the roots of patriotism lie in the simple fact that God told Adam and Eve to “fill the earth and subdue it,” but then gave them a special, local place, a garden, in which to carry out that mandate. The whole earth was the Lord’s, and they knew it, but he gave these particular people a particular place within his world to love and cultivate. If their garden had had a flag, I cannot help thinking the sight of it whipping in the breeze would have stirred them in a way that another bit of colored cloth could not have.

But patriotism grows out of other biblical principles as well. What about gratitude? Our country is far from perfect, but we still have much to be thankful for. Wipe away every bit of national history and law and government; is that new world a better place? If not, then you have reason to be grateful for the nation you inhabit. And what about gratitude to those who sacrificed to build and protect that nation? Our national anthem’s “rocket’s red glare… bombs bursting in air” were once more than lyrics, and the men who dodged those missiles did so in part for our sake. When the Fifth Commandment reminds us to honor our father and our mother, it is not only talking about immediate progenitors.

It is true, of course, that our fathers and mothers were far from perfect. Loving our country does not require that we admire everything she has ever done, any more than loving your family requires you to affirm every decision your parents ever made. Neither does it require that we go along with everything our nation does today. Martin Luther King, Jr. knew what he was doing when he began his “I Have a Dream” speech by reminding his audience of Abraham Lincoln and “the architects of our republic [who] wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence.” The citizen who most honors his nation will be the most committed to eradicating any ugly blots upon her character.

There is no denying that racism and pride have often dressed as patriotism (there is truth in Samuel Johnson’s observation that patriotism is the last refuge of the scoundrel) but the answer to a distorted patriotism is a healthier one. Don’t confuse your country with God; don’t confuse her with the Church; don’t excuse her faults; but remember that she is your country, and love her accordingly.

Header photo by Kurt Magoon under CC BY-SA 2.0, cropped